Salmonella

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the bacterium. For the disease, see Salmonellosis.

| Salmonella | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Scientific classification | |

| Superkingdom: | Bacteria |

| Kingdom: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Proteobacteria |

| Class: | Gammaproteobacteria |

| Order: | Enterobacteriales |

| Family: | Enterobacteriaceae |

| Genus: | Salmonella Lignieres 1900 |

| Species | |

|

S. bongori S. enterica |

|

Salmonellae are found worldwide in both cold-blooded and warm-blooded animals, and in the environment. They cause illnesses such as typhoid fever, paratyphoid fever, and food poisoning.[1]

Contents

Features

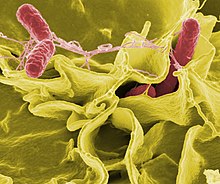

Salmonella are non-spore-forming, predominantly motile enterobacteria with diameters around 0.7 to 1.5 µm, lengths from 2 to 5 µm, and peritrichous flagella (flagella that are all around the cell body).[2] They are chemoorganotrophs, obtaining their energy from oxidation and reduction reactions using organic sources, and are facultative anaerobes.Taxonomy

The genus Salmonella is part of the family of Enterobacteriaceae. Its taxonomy has been revised and has the potential to confuse. It comprises two species, Salmonella bongori and Salmonella enterica, the latter of which is divided into six subtypes: enterica, salamae, arizonae, diarizonae, houtenae and indica.[3][4] The taxonomic group contains more than 2500 serovars, defined on the basis of the somatic O (lipopolysaccharide) and flagellar H antigens (Kauffman–White classification). The full name of a serovar is given as, for example, Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium, but can be abbreviated to Salmonella Typhimurium. Further differentiation of strains may be achieved by antibiogram and by supra- or subgenomic techniques such as pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) and increasingly by whole genome sequencing (WGS) in order to assist clinicoepidemiological investigation. On the basis of host preference and disease manifestations in man, the Salmonellae have historically been clinically categorized as invasive (typhoidal) or non-invasive (non-typhoidal Salmonellae or NTS).[5]History

The story of the term Salmonella started in 1885 with the discovery of the bacterium Salmonella enterica (var. Choleraesuis) by medical research scientist Theobald Smith. At the time Theobald was working as a research laboratory assistant in the Veterinary Division of the United States Department of Agriculture. The department was under the administration of Daniel Elmer Salmon, a veterinary pathologist, and that is for whom the Salmonella was named.[6]During the search for the cause of hog cholera it was proposed that the causal agent be named Salmonella. While it happened eventually that Salmonella did not cause that cholera (its enteric pathogen was actually a virus),[7] it turned out that all species of the bacterial genus Salmonella cause infectious diseases. In 1900 J. Lignières re-adopted the name for the many subspecies of Salmonella, after Smith's first type-strain Salmonella cholera.

Detection, culture and growth conditions

Most subspecies of Salmonella produce hydrogen sulfide,[8] which can readily be detected by growing them on media containing ferrous sulfate, such as is used in the triple sugar iron test (TSI). Most isolates exist in two phases: a motile phase I and a nonmotile phase II. Cultures that are nonmotile upon primary culture may be switched to the motile phase using a Cragie tube.[citation needed]Salmonella can also be detected and subtyped using PCR[9] from extracted salmonella DNA, various methods are available to extract salmonella DNA from target samples.[10]

Mathematical models of salmonella growth kinetics have been developed for chicken, pork, tomatoes, and melons.[11][12][13][14][15] Salmonella reproduce asexually with a cell division rate of 20 to 40 minutes under optimal conditions.[citation needed]

Salmonella lead predominantly host-associated lifestyles, however the bacteria were found to be able to persist in a bathroom setting for weeks following contamination, and are frequently isolated from water sources, which act as bacterial reservoirs and may help to facilitate transmission between hosts.[16] The bacteria are not destroyed by freezing,[17][18] but UV light and heat accelerate their demise—they perish after being heated to 55 °C (131 °F) for 90 min, or to 60 °C (140 °F) for 12 min.[19] To protect against Salmonella infection, heating food for at least ten minutes at 75 °C (167 °F) is recommended, so the centre of the food reaches this temperature.[20][21]

The bacteria of Salmonella can be found in the digestive tracts of humans and animals, such as birds and reptiles. "Unusual serotypes of Salmonella have been associated with the direct or indirect contact with reptiles (for example, lizards, snakes turtles, and iguanas)." Food and water can also be contaminated with the bacteria by coming in contact with the feces of infected people or animals.[22]

Salmonella nomenclature

Initially, each Salmonella "species" was named according to clinical considerations,[23] e.g., Salmonella typhi-murium (mouse typhoid fever), S. cholerae-suis. After it was recognized that host specificity did not exist for many species, new strains (or serovars, short for serological variants) received species names according to the location at which the new strain was isolated. Later, molecular findings led to the hypothesis that Salmonella consisted of only one species,[24] S. enterica, and the serovars were classified into six groups,[25] two of which are medically relevant. As this now-formalized nomenclature[26][27] is not in harmony with the traditional usage familiar to specialists in microbiology and infectologists, the traditional nomenclature is common. Currently, there are two recognized species: S. enterica, and S. bongori. In 2005 a third species, Salmonella subterranean, was thought to be added, but this has since been ruled out and is seen as another serovar.[28] There are six main subspecies recognised: enterica (I), salamae (II), arizonae (IIIa), diarizonae (IIIb), houtenae (IV), and indica (VI).[29] Historically, serotype (V) was bongori, which is now considered its own species.The serovar, i.e., serotype, is a classification of Salmonella into subspecies based on antigens that the organism presents. It is based on the Kauffman-White classification scheme that differentiates serological varieties from each other. Serotypes are usually put into subspecies groups after the genus and species, with the serovars/serotypes capitalized, but not italicized: An example is Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. More modern approaches for typing and subtyping Salmonella include DNA-based methods such as pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), Multiple Loci VNTR Analysis (MLVA), Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) and multiplex-PCR-based methods.[30][31]

One strain of Salmonella that has recently been emerging in the United States is Salmonella Javiana. "An outbreak occurred in 2002, there were 141 cases that occurred among the participants of the U.S. Transplant Games. Out of the 141 cases, most of the cases were either transplant recipients (34%) or people receiving immunosuppressive therapy (32%)". There is an increasing number of Salmonella serotypes that are multidrug resistant (MDR), which was identified by the CDC's National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System.[32]

Salmonella as pathogens

Salmonella species are facultative intracellular pathogens.[33] Many infections are due to ingestion of contaminated food. They can be divided into two groups—typhoidal and nontyphoidal Salmonella serovars. Nontyphoidal serovars are more common, and usually cause self-limiting gastrointestinal disease. They can infect a range of animals, and are zoonotic, meaning they can be transferred between humans and other animals. Typhoidal serovars include Salmonella Typhi and Salmonella Paratyphi A, which are adapted to humans and do not occur in other animals.Nontyphoidal Salmonella

See also: Salmonellosis

Infection with nontyphoidal serovars of Salmonella will

generally result in food poisoning. Infection usually occurs when a

person ingests foods that contain a high concentration of the bacteria.

Infants and young children are much more susceptible to infection,

easily achieved by ingesting a small number of bacteria. In infants,

infection through inhalation of bacteria-laden dust is possible.The organism enters through the digestive tract and must be ingested in large numbers to cause disease in healthy adults. An infectious process can only begin after living salmonellae (not only their toxins) reach the gastrointestinal tract. Some of the microorganisms are killed in the stomach, while the surviving salmonellae enter the small intestine and multiply in tissues (localized form). Gastric acidity is responsible for the destruction of the majority of ingested bacteria, however Salmonella has evolved a degree of tolerance to acidic environments that allows a subset of ingested bacteria to survive.[34] Bacterial colonies may also become trapped in mucus produced in the oesophagus. By the end of the incubation period, the nearby cells are poisoned by endotoxins released from the dead salmonellae. The local response to the endotoxins is enteritis and gastrointestinal disorder.

"Salmonella javiana causes 4% of nontyphodial Salmonella infections in the United States each year." [35]

Invasive non-typhoidal salmonella disease

While in developed countries, nontyphoidal serovars present mostly as gastrointestinal disease, in sub-Saharan Africa these serovars create a major problem in bloodstream infections, and are the most commonly isolated bacteria from the blood of those presenting with fever. Bloodstream infections caused by nontyphoidal salmonellae in Africa were reported in 2012 to have a case fatality rate of 20–25%. Most cases of invasive nontyphoidal salmonella infection (iNTS) are caused by S Typhimurium or S Enteritidis. A new form of Salmonella Typhimurium (ST313) emerged in the southeast of the continent 75 years ago, followed by a second wave, which came out of central Africa 18 years later. The second wave of iNTS possibly originated in the Congo Basin, and early in the event picked up a gene making it resistant to the antibiotic chloramphenicol. This created the need to use expensive antimicrobial drugs in areas of Africa that were very poor, thus making treatment difficult. The variant is the cause of an enigmatic disease in sub-Saharan Africa called invasive non-typhoidal salmonella (iNTS), which affects Africa far more than other continents. This is thought to be due to the large proportion of the population with some degree of immune suppression or impairment due to the burden of HIV, malaria and malnutrition, especially in children. Its genetic makeup is evolving into a more typhoid-like bacteria, able to efficiently spread around the human body. Symptoms are reported to be diverse, including fever, hepatosplenomegaly, and respiratory symptoms, often with an absence of gastrointestinal symptoms.[36]Nontyphoid Salmonella, has approximately 2,000 serotypes and may be responsible for as many as 1.4 million illnesses in the United States each year. People who are at risk for severe illness include infants, elderly, organ-transplant recipients, and the immunocompromised.[37]

Typhoidal Salmonella

See also: Typhoid fever and Paratyphoid fever

Typhoid fever is caused by Salmonella serotypes which are strictly adapted to humans or higher primates—these include Salmonella Typhi,

Paratyphi A, Paratyphi B and Paratyphi C. In the systemic form of the

disease, salmonellae pass through the lymphatic system of the intestine

into the blood of the patients (typhoid form) and are carried to various

organs (liver, spleen, kidneys) to form secondary foci (septic form).

Endotoxins first act on the vascular and nervous apparatus, resulting in

increased permeability and decreased tone of the vessels, upset thermal

regulation, vomiting and diarrhea. In severe forms of the disease,

enough liquid and electrolytes are lost to upset the water-salt

metabolism, decrease the circulating blood volume and arterial pressure,

and cause hypovolemic shock. Septic shock may also develop. Shock of mixed character (with signs of both hypovolemic and septic shock) are more common in severe salmonellosis. Oliguria and azotemia develop in severe cases as a result of renal involvement due to hypoxia and toxemia.Global monitoring

In Germany, food poisoning infections must be reported.[38] Between 1990 and 2005, the number of officially recorded cases decreased from approximately 200,000 to approximately 50,000 cases. In the United States, about 50,000 cases of Salmonella infection are reported each year.[39] According to the World Health Organization, over 16 million people worldwide are infected with typhoid fever each year, with 500,000 to 600,000 fatal cases.[citation needed]Molecular mechanisms of infection

Mechanisms of infection differ between typhoidal and nontyphoidal serovars, owing to their different targets in the body and the different symptoms that they cause. Both groups must enter by crossing the barrier created by the intestinal cell wall, but once they have passed this barrier they use different strategies to cause infection.Nontyphoidal serovars preferentially enter M cells on the intestinal wall by bacterial-mediated endocytosis, a process associated with intestinal inflammation and diarrhoea. They are also able to disrupt tight junctions between the cells of the intestinal wall, impairing their ability to stop the flow of ions, water and immune cells into and out of the intestine. The combination of the inflammation caused by bacterial-mediated endocytosis and the disruption of tight junctions is thought to contribute significantly to the induction of diarrhoea.[40]

Salmonellae are also able to breach the intestinal barrier via phagocytosis and trafficking by CD18-positive immune cells, which may be a mechanism key to typhoidal Salmonella infection. This is thought to be a more stealthy way of passing the intestinal barrier, and may therefore contribute to the fact that lower numbers of typhoidal Salmonella are required for infection than nontyphoidal Salmonella.[40] Salmonella are able to enter macrophages via macropinocytosis.[41] Typhoidal serovars can use this to achieve dissemination throughout the body via the mononuclear phagocyte system, a network of connective tissue that contains immune cells, and surrounds tissue associated with the immune system throughout the body.[40]

Much of the success of Salmonella in causing infection is attributed to two type three secretion systems which function at different times during infection. One is required for the invasion of non-phagocytic cells, colonization of the intestine and induction of intestinal inflammatory responses and diarrhoea. The other is important for survival in macrophages and establishment of systemic disease.[40] These systems contain many genes which must work co-operatively to achieve infection.

The AvrA toxin injected by the SPI1 type three secretion system of Salmonella Typhimurium works to inhibit the innate immune system by virtue of its serine/threonine acetyltransferase activity, and requires binding to eukaryotic target cell phytic acid (IP6).[42] This leaves the host more susceptible to infection.

Post a Comment